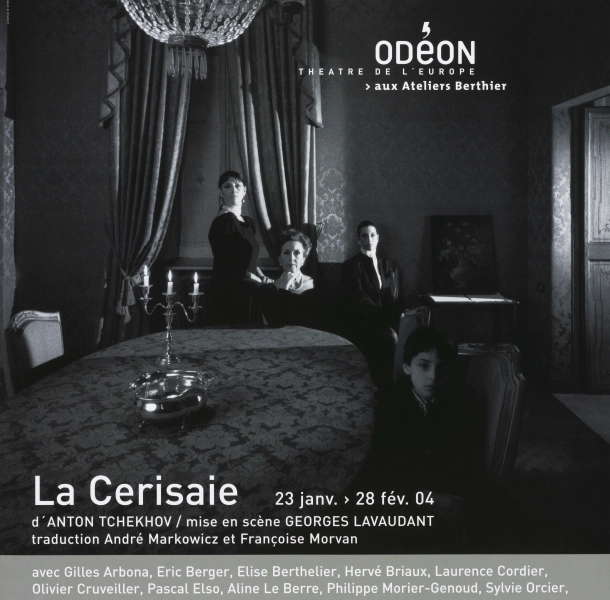

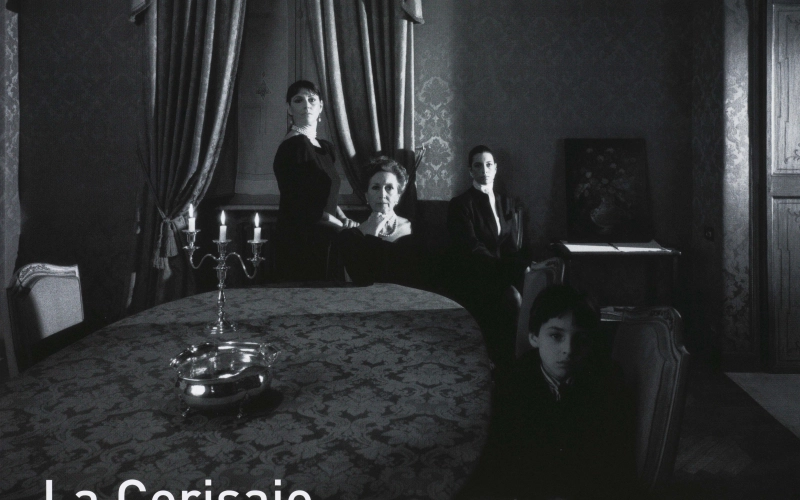

La Cerisaie / The Cherry Orchard

January 23 2004 to February 28 2004

Berthier grande salle

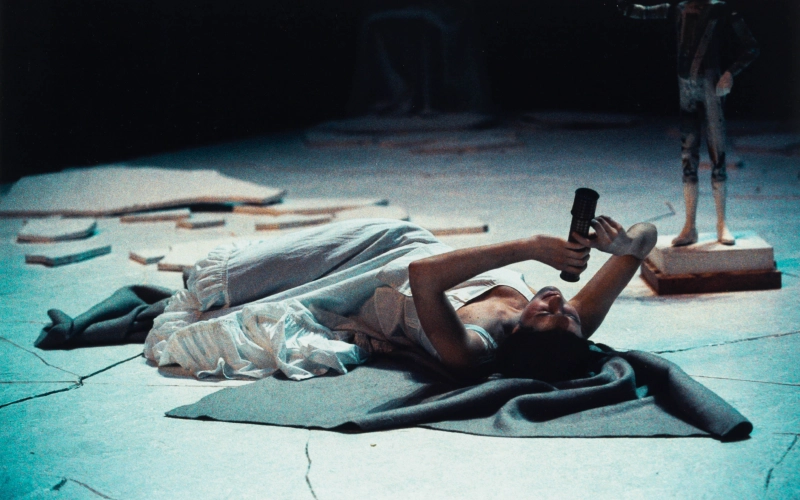

More than ten years after Platonov, which met with great critical acclaim, Georges Lavaudant and the Odéon theatre company are returning to Chekhov, and moving from the first to the last play, premiered with the author in attendance just on a century ago, on January 17, 1904, on the evening of his forty-fourth and last birthday.

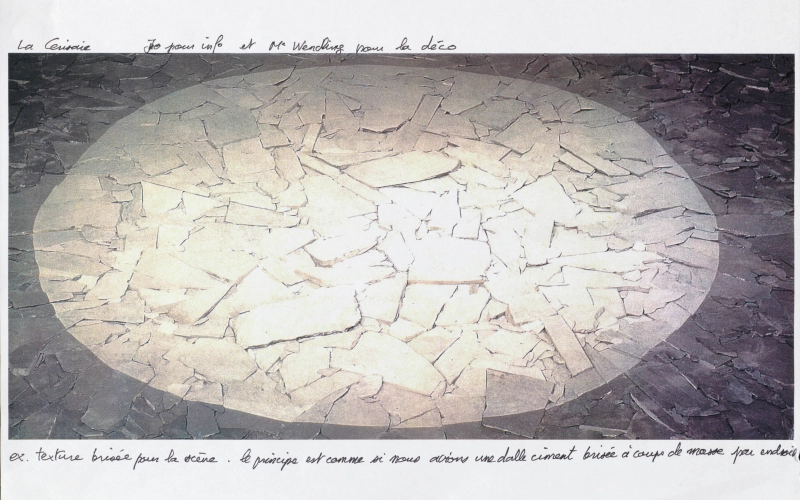

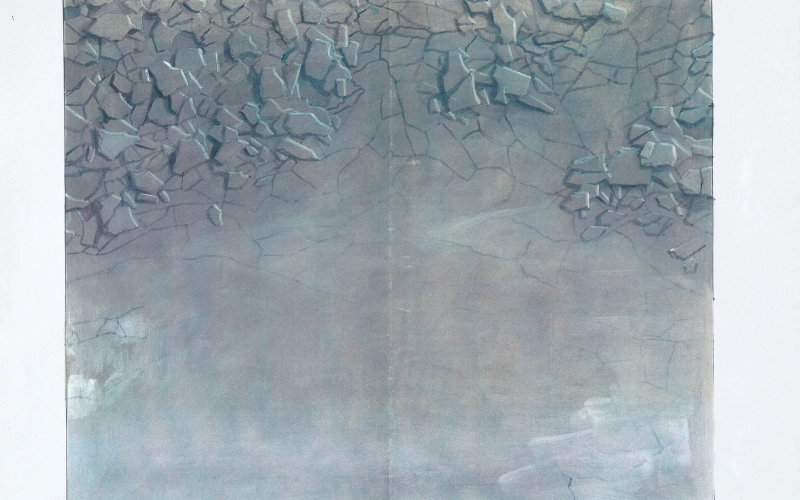

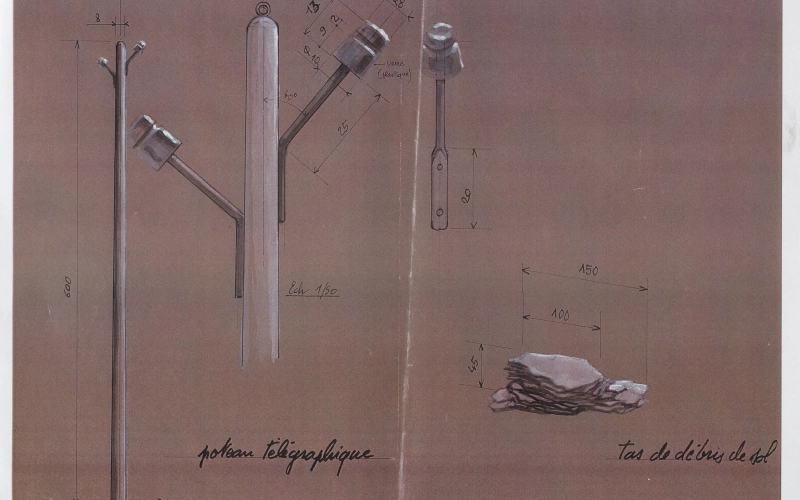

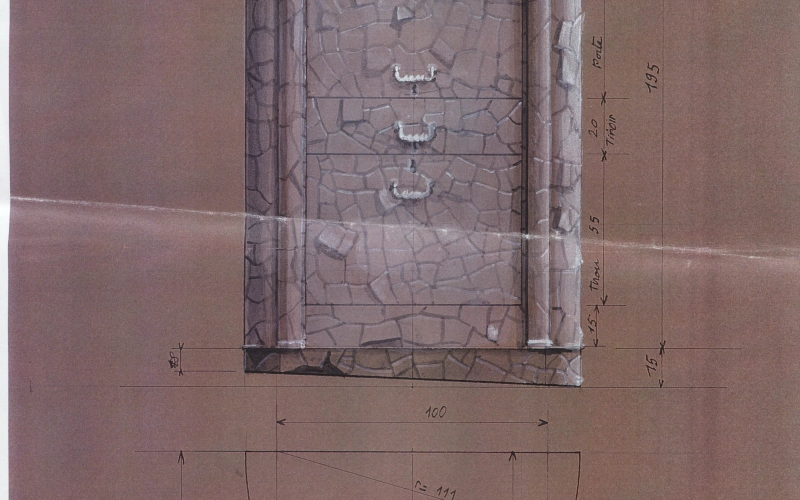

The Cherry Orchard. A delicately pale orchard, the precious garden of yesteryear, where the silhouette of the mother can still be seen passing by at dawn. But there are also the unsellable cherries, and even they only fruit once every two years. In this timeless shelter is the venerable bookshelf still presiding in the children's bedroom, where, forty years later, old Feers still rues the passing of the age of the master and servant. There is also the legacy of debt, neglect and abandonment left by the owner. Without this inalienable treasure, Liubov cannot understand her own life, here where her father, mother and grandfather lived before her, the life she rediscovers with the same emotional force when returning from Paris after five years. And there is the domain where her seven-year-old son drowned in the river. Twelve lives, interwoven: a mother, her brother and her two daughters, a few servants, a neighbour, a student, a peasant's son named Lopakhin who has gone into business, plus a view of Russia, drawn up in masterly style, one year before the first Revolution - the aristocracy is on the run, or running from reality, as a new middle class of entrepreneurs continues to rise. Four points in time across the seasons, from full flower in the mist of May to the bare dark trunks struck by the axe in the October sunlight. The Cherry Orchard is the swan song of a genius who knew the end was near. He described it, and aptly so, as a "comedy"; in fact all the elements of satire can be seen quite clearly, a certain aura of silent understanding envelops all the characters, as if feelings and detachment could no longer be distinguished. Here is a celebration of time, of pasts and futures with varying degrees of illusion, which each one can take away, a final tribute to beauty destined to fade, a greeting for death always lurking in the background, albeit a greeting with a certain smile which is not just ironic; after all, where is the tragedy? Here is a poem shining with ineffable light, requiring great delicacy of approach, melancholy but never self-indulgent, dark in its buoyancy, set around an invisible garden facing inevitable destruction.