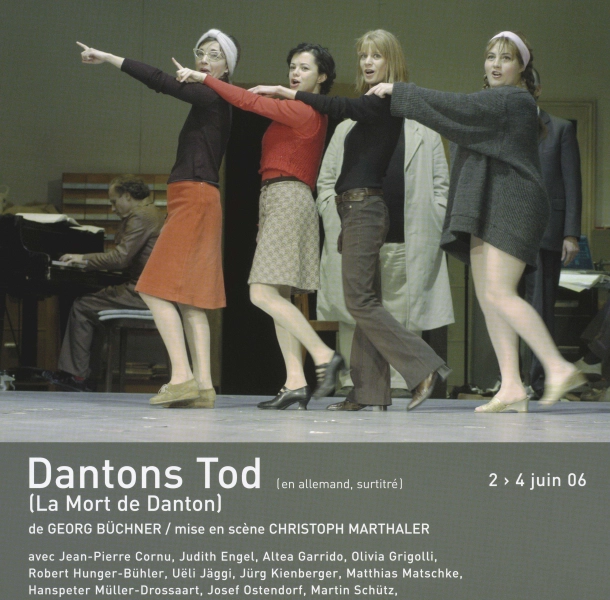

Dantons Tod (Danton's Death)

June 02 2006 to June 04 2006

The man who writes Danton's Death isn't even 22-years-old. Forced to remain quiet in Darmstadt - he knows that the police are watching him since publishing a revolutionary attack, The Hessian Messenger - he busies himself by reading the ten volumes of Adolphe Thiers' History of the French Revolution in the grand-ducal library. In less than two months, early 1835, Büchner writes a drama with an elliptical nervousness, the secret of which had seemed lost since the Elizabethans. As if indifferent to the real-life conditions of staging, he alternated interior and exterior scenes, stages of all sizes, popular language and political rhetoric, with no other rules than his subject: the unbending trajectory that led Danton and his friends to the guillotine between March 30 and April 5, 1794. Nothing less, in other words, than a crucial moment in the French Revolution, and thus world history.

Büchner didn't only borrow staging methods from Shakespeare. He was also inspired by his climates. Robespierre haranguing the crowd makes us think of Menenium Agrippa calming the rebel plebeians in Coriolanus. Danton, who sometimes consents, and sometimes refuses, to let himself be drawn into this sort of horrible funnel that leads him towards an abyss, perhaps remembers Richard II. Büchner goes even further, by sometimes giving his hero a discreetly Christ-like aura: in his final hours of captivity, Danton remains alone to keep watch among his companions, like Jesus on Mount Olive. And he too had his Judas. But Danton is neither a king, nor a God - these steadfast figures can no longer provide a pose that suits him. He is only a man, supremely eloquent, who, one fine day, maybe because of visiting prostitutes, especially because of listening to them, collided with the vacuity of grandiloquence. So in what name does he approach execution?

"We are poor musicians, and our bodies, the instruments. Do the discordant sounds we produce have any other goal than to climb, always climb, until finally gently fading away like a sigh of sensual delight, dying at celestial ears?" With this question, Büchner finishes off the Enlightenment. Each confronts death, which belongs only to himself, in an abeyance of meaning that is his responsibility alone. Danton's death belongs to him like a mystery.

In this tremendous sway of events, the Revolution itself finishes by being undermined. Was Robespierre right to condemn Danton? Is Terror one of the veils that covers Reason in History, or the first effect of panic from the collapse of all meaning? The least of surprises that Büchner reserves for us is that he doesn't say. And Marthaler doesn't either, he who stands, like we all do, in the wake of so many other revolutions, bourgeois or socialist, which all saw their ideals betrayed or led astray. As time slows down and reaches its end, whereas history and modern theater open, space empties, leaving only Danton and his friends to face death, which will offer a last drink before lowering the iron curtain. To tell this cruel and true story in his own way, Marthaler gives his disenchanted tonality a euphoric faith in life, to the sound of the songs of all revolutions.